Don "Sully" Sullivan

Over 92 years ago the 1932 Ford and its innovative engine was introduced to world. HRD has a very special connection with this historic accomplishment in the name of Don ‘Sully’ Sullivan. You see, Don Sullivan was one of five engineers picked personally by Henry Ford to design and develop Ford’s Flathead V-8. And, Don Sullivan also happens to be my Grandfather. He was a hell of a guy and a great engine designer that thrived on making things work against overwhelming constraints. He could take ‘boat anchors’ and turn them into explosive power plants of horsepower. He was also gifted with a charming twinkle in his eyes that made those that worked with him enthusiastic and energized.

As a good overall introduction to Sully’s career, I picked from many articles written about him, ‘Henry Ford’s Wild Irishman’, by Dave Emanuel. This appeared in the 1989 February issue of Super Ford. This article has a particularly good account of the early design effort of the Flathead V-8.

Henry Ford’s Wild Irishman

By Dave Emanuel

SUPER FORD, February 1989

"I've been fired from Ford more times than most people have jobs."

You would expect a statement like that to be made with a good deal of bitterness. But when Don Sullivan talks about his long career at Ford Motor Company, it's always with a sense of pride. What's more, his fierce loyalty to Henry Ford and the company he founded is unshakeable.

Reflecting on his early days with Ford and his frequent firings, he says, "I can't tell you why, but they'd come and say, 'You know you're fired, don't you?' When that happens, you leave before they throw your lunch bucket over the fence. Then in a few days, some big goon who looks like Jess Willard comes up in a Model A car, pounds on the door and says, 'You Sullivan? Come along with me.' And then I'd go back to work. I don't know anything about how all that happened."

Apparently, Henry Ford had taken a liking to the young engineer, and when he found Sullivan was not on the job, he left instructions to hire him back. Henry Ford worked in strange ways, on professional as well as personal levels; he rarely took a direct approach. Sullivan recalls a time when he was trying to fix an outboard motor for a fellow worker. "I was trying to find out why it wouldn't start, and Mr. Ford walks in the back door. I almost died. He said, 'What's the matter?' And I said, 'Oh, I can't get this thing started.' He walked on and didn't say a thing. I was so scared I was shaking. So I unhooked the dam thing and took it out to my car. I shook all afternoon. Then around quitting time, one of these muscle men sticks his head "in the back door and hollers, "Where's da guy dat's got da outboard motor. He was so loud you could here him up at the Dearborn Inn. I told him it was in my car. He said he had to have it. So I went out and gave it to him and he took off.

"Howard Salley, the guy who owned the motor, asked me what happened, and I told him some great big guy came in and asked me for the motor. He said, 'You didn't tell him who's it was, did you?' I told him he thought it was mine and Howard said, 'Good.'

About a week later, the guy came back looking for me, and I thought they were going to take me out and hang me by the thumbs. But he just said that he had it out in the car. And there the motor was, and it had new stickers all over it. Mr. Ford had had the whole thing rebuilt."

At age 84, Sully, as he is known throughout the industry, has been working for Ford for almost 60 years. His experience extends from the design of the original flathead V-8 to the latest addition to the Ford racing stables - the SVO V-6. As a consulting engineer for Ford's Special Vehicles Operation, Sully is at his desk five and a half days a week - not just spending time but making things happen.

Don Sullivan's career has come full circle since 1969, when he reached the mandatory retirement age of 65. After some 40 years in the employ of Ford and countless engineering successes, he had reached a fork in the road. One branch would take him to the ennui of retirement, the other would lead him to a new occupation as an engineering consultant. With his vast experience and excellent reputation, his services were much in demand. But his loyalty was always with Ford, so when an opportunity to work in the SVO group arose in 1981, Sully returned to where his heart had always been. He's been there ever since.

A living legend within the motorsports world, Sullivan avoids publicity and tends to downplay his accomplishments. But whenever there was a problem with a Ford high-performance program, more often than not it was Sullivan who came up with the solution. From pre-war efforts at Indy, to Pikes Peak hill climbs, turbocharged Indy V-8s and LeMans in the '60s, it has been Sully who has turned disaster into victory. And when Carroll Shelby was building Cobras and Shelby Mustangs, he called Sully when he needed assistance with Ford parts and components.

Don Sullivan's career with Ford began April 12, 1928. With a degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Michigan, Sully began working on engine development almost immediately. And it's the early years, working directly with Henry Ford on the design of the first flathead V-8, that he remembers most fondly. Back then, engineering was carried out a bit differently than today. A group of 30 to 40 draftsmen would be charged with designing components for all the cars and trucks sold under one name plate. Work was assigned on a somewhat random basis, and as Sully puts it, "You had a chief draftsman who kept track of what everyone was doing, and you just did whatever had to be done. One day you might be laying out a radiator, and the next day you'd be working on a chassis part. And they kept you busy. There was always a pile of work waiting to be done."

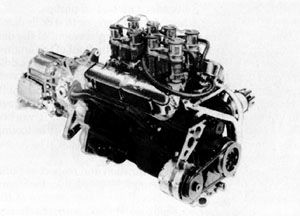

Sullivan first worked directly with Henry Ford, who called him "my wild Irishman," in 1930 when he was involved in the then highly secretive V-8 project. To keep the project under wraps until he was ready to expose it, Henry Ford had moved the entire works to Greenfield Village where an assortment of noteworthy buildings had been moved from all over the country and assembled as a tribute to Americana. A cadre of five engineers set up shop in the building that had once been Thomas Edison's laboratory in Fort Meyers, Florida. It was here that they proceeded to bring Ford's first V-8 to life.

As Sully recalls, Henry Ford was involved with the project on a day to day basis. "Every day, Mr. Ford would come in the back door and say, 'Hello boys,' and then start looking things over. The man who ran the job was Carl Schultz, but very little communication came through him. He took care of some of the basic things, but Mr. Ford took care of all the details. I remember one day Mr. Ford came by and said, 'What are you doin'?' - he always asked you, 'What are you doin'?' I said, 'Making a connecting rod.' At the time there were a bunch of big, crude vertical steam engines right outside, and he said, 'For what, one of those things out there?' Then he just walked away.

"So I made a real thin connecting rod. Everybody thought it would never work, but that's what he wanted. It wasn't weight consciousness, he was concerned about the amount of steel that would be needed to make an engine because he knew we'd be building millions of them. They had to develop a special steel, but we broke very few of those rods." As he was prone to do, Henry Ford got what he wanted. According to Sully, everyone knew that Henry Ford ran the shop. And even if it was wrong, it was right if Mr. Ford wanted it that way. Although Sullivan recalls that Ford was a very reasonable man to work with, there's evidence that his tunnel vision did create problems. One of his major concerns in the design of the flathead V-8 was with keeping the engine simple. Consequently, early production models had the water pump mounted on top where it was accessible. But the pump would cavitate in that position and ultimately, after a considerable amount of "band-aid engineering," it had to be relocated to provide adequate cooling.

By most accounts, Henry Ford was more than a little eccentric, but Sully has a different point of view. He says, "He wasn't wrong about very many things. I thought a lot of times he was out of his mind, but it would usually turn out that he wasn't far off. He wasn't eccentric, he was just very positive in his thinking. Now if you didn't like what he was thinking, he was eccentric. He was concerned about the product more than anything else. Things had to be done so that anybody could fix the engine, and it had to be designed so that you couldn't do things wrong."

In his quest for simplicity, Henry Ford tried to eliminate as many components as possible from the flathead V-8. Sully recalls that the pre-production engines had no oil pump and no water pump. Thermo-siphoning controlled coolant flow and cup-like shaping of the ends of the crankshaft counterweights splashed oil inside the engine. Sully didn't much care for the system, and during check-out runs with test driver Howard Salley at the wheel, the engines failed routinely. Knowing that a splash system was inadequate, Sully had the driver swing the car from side to side as if he were driving through a slalom. With oil sloshing back and forth across the pan and staying out of reach of the crankshaft dippers, it wasn't long before oil starvation led to engine failure. Consequently, production flathead versions all had oil pumps.

Another facet of the engine that Sully didn't care for was the initial placement of the distributor, down low on the front of the engine. He states, ''You couldn't run through a puddle of water without the distributor getting wet. The oil pump was driven by a vertical shaft, and there had to be an idler gear between the cam gear and the oil pump. It worked out that there would be very little tooling change to relocate the distributor. That's how it got moved up on top."

As much admiration and respect as Sullivan has for Henry I, he has dislike for Henry II. When Henry II took over control of the company, Sullivan didn't see much of a change. He states, "The 'Whiz Kids' [a group of Henry II's college buddies] ran the company. That *&I\%! kid didn't do anything; it was McNamara and Breech and those guys. He wouldn't be tied down running the company. He gets a lot of credit, but his mind was never on business."

Sully's feelings about Henry II also stem from his attitude towards his grandfather. Not only did Henry II auction off a lot of the furnishings in Fairlane (Henry Ford's mansion), he senselessly destroyed a lot of records documenting family and company history. But what irritates Sully most is a comment Henry II made after Henry I had passed away. "A group of people were taking a tour of Fairlane and they came across a room loaded with books. Someone said, 'Your grandfather must have liked to read' and Henry Ford II said, 'I don't think the bastard ever read a book.' The only one who was loyal was Mrs. Edsel Ford [Henry II's mother]. She turned all her interests over to a foundation to preserve the mansion."

As might be expected, Henry II's treatment of Lee Iacocca didn't set well with Sully either. He states, "Iacocca was a hell of a good guy; he worked his way up through the company. The way I get the story, the trouble began when Henry Ford II asked him to take one of his sons and groom him to run the company someday. Iacocca told him that he didn't run a kindergarten, he built cars. That's what started all the trouble. He had a hell of a time figuring out how to get rid of Iacocca, and 1 don't know how he came up with the solution. Somebody must have advised him, because he wouldn't, couldn't have come up with it himself."

After finishing up the flathead and a few other projects, Sully became resident engineer at the Cleveland engine plant where six-cylinder and 256 cubic-inch Mercury flatheads were built. But by the early '50s, he had been transferred back to Dearborn to apply his talents to Ford's NASCAR efforts. Later, he was charged with improving camshaft, valve train and oiling system design on high-performance versions of the 292 and 312 Y-block V-8s. However, before he could bring about any significant changes, the 1957 AMA ban on racing took effect, and performance activities were temporarily put on the back burner.

Although the classic American rivalry is between Ford and Chevrolet, Sully remembers that Chrysler and Pontiac were the chief competitors in the early '50s. Remembering the teams fielded by Carl Keikheifer he states, "I'll tell you they were bad news. That old Keikheifer was a cheater and wouldn't quit. He had Chrysler engines that weren't even painted, they came right from Highland Park [Chrysler headquarters] all ready to go."

With the 1957 factory agreement "banning" racing activities, Ford, GM and Chrysler ended their visible support of NASCAR race teams. And while the performance image was downplayed, racing activities merely shifted from the front door to the back door. By the early '60s, most of the automakers were playing the same game, paying lip service to the agreement while" actively supporting race teams as "research and development" efforts.

Ford had introduced the "FE" engine series in 1958 and from the original 352, the engine had grown to 390, 406 arid finally 427 cubic inches. It was the 427 that ultimately carried Ford to victory at LeMans, and Sullivan became involved in grooming the engine for road racing. With its roots in NASCAR and drag racing, the racing version of the 427 wasn't particularly well suited for the road course.

"We had low-riser, medium-riser and high-riser heads for the 427 and all that stuff was a disaster;" said Sully." At that time, it had to be big to be better, and they had the ports way too big. The carburetor was way too big - you had no velocity and you got no performance at all because it had no torque. But it had a big horsepower number. Everybody had to have a big power number. They had the same problem with camshafts - no torque. You couldn't use those engines in road racing because they just didn't nave enough torque. The 302 we used in Trans-Am had the same problem. The ports were too big and so was the carburetor. I designed a new camshaft to make more torque, and the guy who was my boss at the time wanted to fire me. He said, 'This hasn't got any power.' I told him that to run the camshaft we had been using, you'd have to have a ten-speed gearbox because you couldn't get off a corner with it. So we used the E2 camshaft and that worked pretty good."

When Ford went to Indy in the '60s, they went with specially built engines based on the 221-289 small-block. As might be expected, Sully was in charge of the project.

Sully's involvement with the LeMans effort centered around the 289 (and, later, the 302) GT40s, but they were overshadowed by the 427s. Although the small-blocks produced excellent power and had good durability, they were no match for the bigger engines.

What Sully remembers most about LeMans is the victory in 1967 and the man he feels is the unsung hero of that effort - Mose Nowland (who still works for Ford in the SVO division). As Sullivan recounts the story, "It was in the middle of the night and the car came into the pits and had a lifter clicking. Now Mose wasn't even supposed to be in the pits, he was just there as an advisor. Anyhow, he just happened to have some rocker screws in his pocket when he was standing behind the wall in the pits. When the car came in and he heard the lifters clicking, he jumped over the wall, grabbed a speed wrench and yanked the valve cover off. He replaced the rocker screw and that's how we won the race. And you know, I've never heard anybody say anything about that."

Although Don Sullivan retired from Ford just a few years after the LeMans effort, he continues to leave his mark on the Ford racing program. He's currently working on the SVO V-6 and at this point he says, "I did all the layouts on the engine, but right now, I'm sweeping up the chaff and making sure that everything is all right. I think that engine is going to work out pretty well."

After 60 years in the business, Don Sullivan should know.

By Dave Emanuel

SUPER FORD, February 1989